Remembering Billy Frank Jr.

I spent one memorable summer afternoon with this giant of Native environmental activism who is back in the news

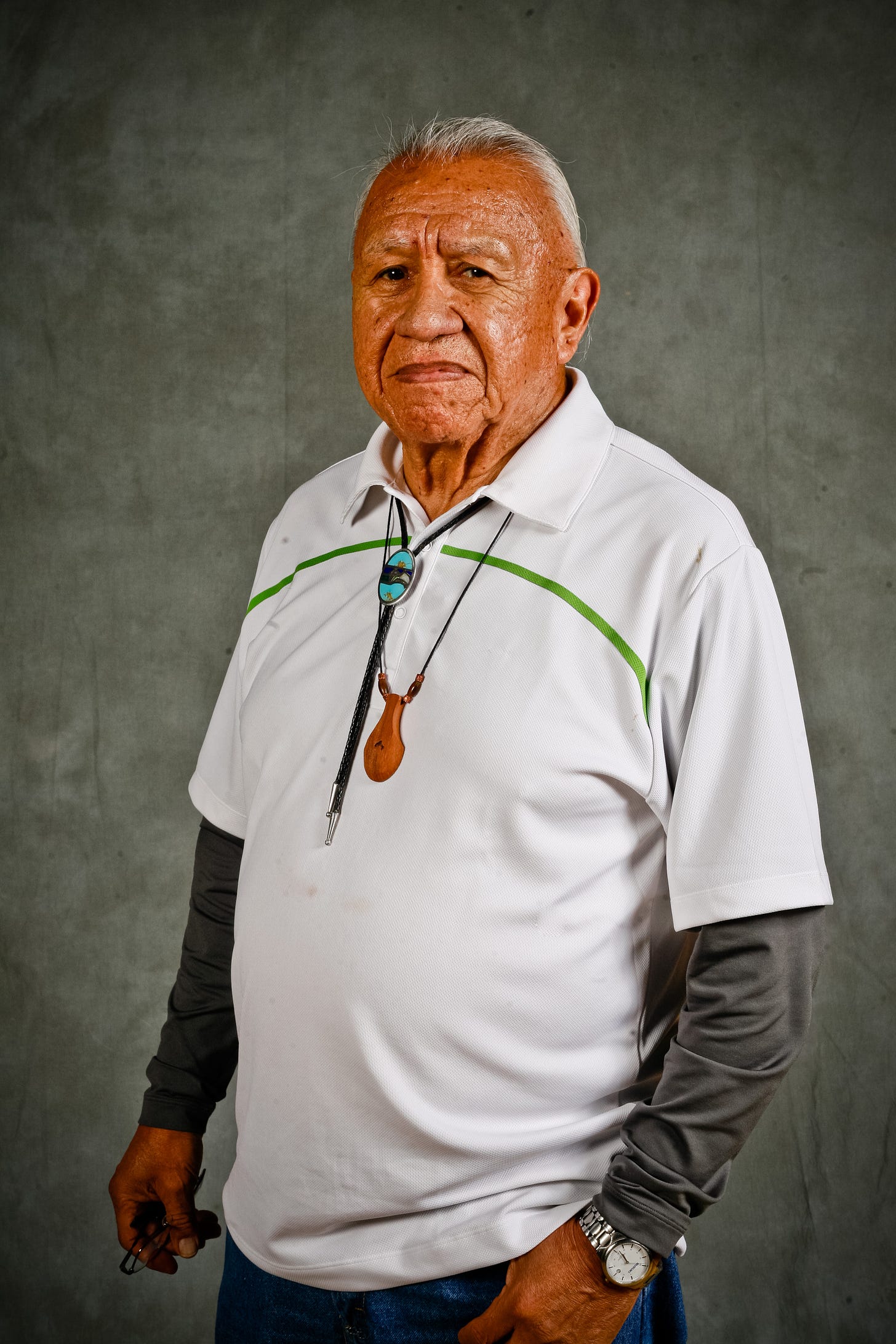

Billy Frank, Jr., March 9, 1931–May 5, 2014

In 2012, I got an unreal assignment. I was sent up the I-5 from Portland to Tacoma, Washington to interview Billy Frank, Jr. for the nonprofit where I worked. A Nisqually tribal member, Billy was a giant of Native environmental activism who was arrested more than 50 times during the 1960s and 70s. His unwillingness to give up eventually spawned historic reform, assuring Washington tribes the right to fish and co-manage salmon. In the decades that followed, Billy led from within the system and was one of our country’s most sincere and effective voices for healthy watersheds, clean water, and flourishing salmon populations. He understood that if tribes had the legal right to fish, then there had to be fish to catch, and that meant the government had a legal obligation to maintain healthy, flowing, unpolluted rivers. But they would not (and will never) do what needs to be done unless Native tribes hold them accountable.

I remember feeling out of my depth. I had a coworker with me—Shawna, a member of the Yurok tribe—and she was also awestruck. But the moment we arrived in the small office of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission where he worked, he did the emotional equivalent of winking at us with his whole body. He laughed and jumped into conversation. He was kind, direct, and open. While he talked about very serious and upsetting things, he would periodically giggle and laugh, as if to say, just because it’s serious doesn’t mean we have to be depressed. He died two years later, at age 83. I only sat with him for a few hours, but he left me with a feeling I hold dear—that sometimes the sharpest, most uncompromising and visionary people are also the goofiest and most loving.

A few days ago, driving over the Willamette, I heard news that Washington State is proposing to place a statue of Billy Frank, Jr. in Washington, D.C. Turns out every state in the U.S. has space for two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection. (Oregon’s are, wait for it, Jason Lee, a Canadian Methodist Episcopalian missionary and pioneer, and John McLoughlin, a French Canadian of the Hudson’s Bay Co. The selection of these long-dead white men as emblems of our state is clearly inappropriate, racist, and out of touch, but may I also note that they are both Canadians!) Billy would replace Marcus Whitman, of Whitmen College, and the Whitman Massacre, whose history is worth reading because he is in a sense the exact opposite of Billy.

“There’s no one better than Billy Frank, Jr., who stood with all of you,” Debra Lekanoff, Democratic Representative from Skagit Valley, told the Washington House State Government & Tribal Committee. Lekanoff, who is a member of the Tlingit tribe and the only Native American woman in the Washington State Legislature, brought the bill forward.

I eagerly await the results of their decision. At the end of the day, it’s only a statue. But it reminded me of my time with him, and in that way, it’s a powerful encouragement to engage with his memory. I thought I would share excerpts of my transcription from the few hours I spent with Billy. It’s admittedly sprawling, but these are his words, as best as I could type them. Rereading this, I could feel what indigenous justice means in a very specific sense. Despite my frequent disillusionment, I know that we do have inspiring national heroes; we just have to get the wrong statues out of the way so we can remember who they are.

June 25, 2012

First, we ceded all this land from Canada to the Columbia River on this side of the mountain, our 20 tribes along the Pacific Coast clean up to Makah. We ceded it to the United States government in 1854 and ’55 so they could build their cities and start [harvesting] natural resources. But now today, there’s no habitat left for our salmon, and there’s no habitat for anything on the rivers anymore. The timber’s cut down, clearcut, they’ve over-allocated all the water, and the dams have been put up. All of this is happening right before our eyes. Now we are co-managers. But we’re 200 years too late. And everything was disappearing as we come on the scene. The habitat’s gone…

When I first got arrested, I was 14. My parents lived up at Muck Creek, across the river on Fort Lewis, and Fort Lewis took two-thirds of that reservation in the First World War. And so my dad moved to the mouth of the river, and he’s got six acres down there below the hill. And that’s where I was born and raised. All we knew was the fish right here. We’re off the reservation. “You can fish anywhere in your usual and accustomed places.” He goes back to that treaty. We’re talking about the treaty all the time. We’re born and raised talking about it. And we’d get on the river and pretty soon we start going to jail. We’re hiding at nighttime. We’d pole up the river, set our net, pole back down before daylight, because the wardens are always looking for us. Then they got to 24 hours a day they were watching us.

I don’t know how the State of Washington has allowed this to happen, but they’re so racist and out of step, they don’t know who the hell we are, don’t know we have a treaty with the United States. The United States let’s this all happen. So I was trying to take them to court. They only take me to local court. This is Thurston County. They’d take me to Pierce County cause they could get a decision over there, so they’d haul us all that way. We went to jail. We just kept going to jail. We did fish ins. And it just got worse and worse. And then Martin Luther King started preparing his march, so we went back there, and we marched with him. “We’re treaty rights Indians out here for treaties,” and that’s how we marched with MLK and Andrew Young. So now we’re in this national scene…

Finally, we’re in Tacoma, we’re having this fish camp at the mouth of the river there right by I-5. And the U.S. attorney was there. They knew we were gonna get busted that day. We didn’t know that. It was another time in history of the State of Washington doing the wrong thing. They gassed us that day. They gassed every one of us. Because we’re fighting on the river. We burnt the bridge down. Now the bridge is still there; it never even burnt. But it looked like it was burning. Giggles. Black smoke going up right in the city of Tacoma. All the creosote was burning off. They thought it was burning. Here’s the state control and county sheriffs and city of Tacoma and game wardens and fishery department, they all come down on us. The rest of us, kids and everything, we went to jail in Pierce County. This is a Saturday. And the jailhouse, I know all these guys. We’ve been going to jail all the time. And here we go get finger printed again, we’re all going to jail, about 200 of us. And the jailers are mad at the State of Washington. “What the hell, we ain’t got no help here.”

The U.S. attorney was there, and they gassed him. And so he said, “well, we’ve got to sue the State of Washington.” So the United States sued the State of Washington on our behalf, and that ended up being the Boldt Decision, and we won. It interpreted the treaties, and a lot of good things came out of that. The Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission was formed there. We coordinate with all the tribes… We have our meeting every month—face to face meeting with all of our tribes. We just left Elwa last week. We stayed up there two days, then we come back. We do a consensus of all of us, to make sure we’re all going the same direction. That’s important. We educate one another. That’s important.

The State of Washington is broke now. They’re not managing anything. They got little enforcement. They’re closing down our hatcheries. We need a change in the government. We need a change for salmon recovery and habitat. Right now, we’re going down. There hasn’t been no change—we haven’t seen anything. So down here there ain’t gonna be no more salmon if we keep going... The Puget Sound is polluted. That ocean from Florence to the Clayton Beach is poisoned the last five years. Salmon coming to shore dead… I sit on a state council. I brought up [the idea of] zero discharge to the council, and they didn’t go for it. Zero discharge is a goal that goes out here a hundred years. And what you do is you’re working on it…

We’re on a course, we’ve been on a course, we’re trying to make change, and we will make that change, we have to because we have to survive. He giggles. For our children, our grandchildren, and all of us together, and we’re going to do it. Then the salmon is going to come back. We’ll see it come back in the next hundred years. It will come back, but we’ll work on it everyday.

We’re picking up a lot of the management of the whole State of Washington now. We’re still going strong. Hopefully we’ll continue to do that in the future. We feel good about what we’re doing.

It’s so important that we have our salmon. This lady right here, gesturing to Shawna, that salmon she’s got in her body, Chinook salmon she’s got up here, that’s all of us. That’s who we are. We’re salmon people. We’ve had our first fish ceremonies… It tells the story of the salmon. He comes home to feed all of us. We depend on him. We have a big ceremony when he comes back. And yeah, we talk about him all the time. We draw pictures about him.

How do you advise young tribal members to help you on this course?

An example is my son. He’s 30 years old, and he’s now vice chairman of Nisqually, our tribe. I raised him and taught him everything I know, as much as I know. Laughing. We’re slowly getting our younger people in there to take over. We have to educate our kids. They have to know about the fight. And stay the course. Don’t get off track and start going this way or that way. Commit yourself to a life.

Tell our story. The same story. Always the same. One of the boys up at Nisqually says, “Hey Billy what are you going to talk about today.” He said, “I’ve heard everything you’ve talked about.” And I said, “I’m gonna tell it the same as I did 50 years ago.” Laughing. “I keep telling you; I tell it over and over, how important the salmon is to our people.”

We should be all telling this story of change. Somebody has to be in charge. Now who the hell is in charge? The president? He’s not in charge. The governors? They’re not in charge. The directors? They’re not in charge. Who is in charge of telling the agencies, all the agencies, you have to follow the guidelines of the treaties of Medicine Creek and Point Elliott or wherever we’re at, and protect the natural resource and bring the habitat back. This is a big giant picture that we’re talking about. And it isn’t no easy one.

You know, people, you have to give a lifetime to what I’m talking about. You can’t just be here today and gone tomorrow. You have to tell this story continually for the rest of your life. That’s what a lot of our people been doing. When you get up in the morning, you continue to do what you have to do. We got to just keep telling that story. If we don’t do it, nobody’s going to do it. The United States? They haven’t done it now. And they’re not gonna do it until we make them do it. It’s not gonna be done overnight. There has to be increments of change. We’ll be way out 100 years of planting trees and getting our watersheds back, getting our oceans clean, and everything. It’s clean water that we need. And water is life.

But we’re gonna do it. We’ve got to do it. I don’t know whether we’ll meet again in 25 or 30 years. You guys will have kids and grandkids and everything, and that’s great, that’s what it’s all about, us doing what we got to do.

I’m 81 now. I should get to live 30 more years. I didn’t say 50 years. Mike said, “God damn, you only said you’re going to live for 30 more years. You’re gonna live for 50 more.”

God dang, thank you for coming up. You guys are young; you’ve got the energy. You’re in a position to slowly turn the tide. All of us together can make these things happen in our time. The directors of the federal government, the directors of the State of Washington, they’ve retired. And I’ve watched them. I went to their retirement ceremonies. They’ve all left. They’ve left us with poison. Us tribes, we can’t leave. The Yuroks are there. Lummis there. Makah. Quinault. Duwamish. Nisqually. We can’t move where the sunshine is or nothing. This is our home here, so we got to save here. We’re staying here with the poison. They’re living happily somewhere, but not around here. We’re left with the mess. That’s not a good document for the people who run this country, but that’s what happened. He laughs. But it left us in charge.