Nancy’s Mom’s Zong, Sticky Rice Dumplings

"These little dumplings have a mythical value in the matriarchal lineage in my family. They represent being a real woman—being able to use your hands and take care of business."

Story by Nancy Wong, interview by Stef Choi, recorded by Lola Milholland

Illustration by Stef Choi

Part of our Inheritance Stories Collective Cookbook, Volume 1

My name is Nancy Wong. I was born in Portland, Oregon in 1986. I live in a little wooden house in Los Angeles, California. Lately I’ve gotten back into hiking around Los Angeles, and since the pandemic I’ve been really digging around in the dirt more. I identify as a person of color and the daughter of immigrants.

The recipe I chose is one I still don’t know how to make: 粽子. In Mandarin: zongzi; in Cantonese: zong. Zong is a sticky rice dumpling with different fillings that is wrapped in these big broad bamboo leaves and steamed, boiled, or how my mom does it—pressure cooked in a big, scary, 15-quart pressure cooker. It’s been in my family for at least three generations, and I’ve always viewed it as the true gateway to becoming a real woman. True womanhood is being able to make 200 sticky rice dumplings to hand out to everyone you know! I’ve watched my mom make these dumplings every year since I was a little teeny tiny girl, watched the way her hands worked to wrap these grains of rice in these slippery bamboo leaves. And as a baby girl, being totally perplexed, just being like, “what is this weird magic??” That perplexed feeling of awe has never gone away!

I’ve tried to learn how to make these at several junctures in my life where I felt like, “ok, I’m old enough and schooled enough and I have enough control over my hands to learn.” At age 5, 9, 12, at 15, 16, 18, 20. I’d try to learn over and over again. My hands would always fail. It wasn’t until this year in the summer that I finally made them, after trying for 34 years with my mom. So I still haven’t made them alone. The idea of me trying to make them alone scares me because it makes me think about the mortality of my mother—that she won’t be there to help me someday. My mom learned to make these dumplings from her grandma, and it wasn’t until her grandma died that she learned how to make them herself. So, I don’t know how to make my recipe by myself.

This dish is typically made for the fifth day of the fifth lunar month in the Chinese lunar calendar. The fifth day of the fifth month in Chinese superstition is a super bad luck day when bad things happen. This really well-respected and well-loved poet drowned himself in the river on this day. When the village heard that he drowned, they all paddled out to the middle of the river to find his body. When they couldn’t find his body, they took out rice and scattered it in the water so the fish would eat rice instead of the poet’s body. They beat on big drums and made splashes in the water with their paddles to protect the poet from bad spirits. That turned into the dragon boat races which are a big thing where my mom grew up and also in Portland, where I grew up. The races represent the villagers paddling out to find their beloved poet. I rowed on the dragon boat team in high school, so that’s another important thing about these dumplings to me. The poet’s ghost asked the villagers to place their rice in a three-pointed dumpling, I don’t know why. I think the number three is pretty lucky in China. And he asked them every year to scatter the rice in those dumplings to feed his soul so he’s not a hungry ghost and to protect his literal body from being eaten.

My mom’s grandma, my great grandma, was a widow and a mother of four or five kids at the age of 25. This was during WWII when the Japanese controlled part of China. My great grandma started wrapping these dumplings and selling them to people in the village to help sustain her family. She was so talented at it that people would travel two or three villages over to buy her dumplings. She would wrap 200 or 300 of them at a time. She had a big old gas/oil drum that she turned into a giant pot to boil them in. When they were finished, she would line them in a big bushel basket, strap them to her back, and walk them into the town to sell them. My mom always associated these with her grandma. And my great grandma’s dumplings are talked about in a mythical way in my family. When I meet my mom’s cousins, great aunts, and great uncles, they all talk about my great grandma’s dumplings and how they still dream about eating them. Many of them have tried to recreate them but everyone fails! I think my mom’s are the version that has gotten the closest in my family. These little dumplings have a mythical value in the matriarchal lineage in my family. They represent being a real woman—being able to use your hands and take care of business.

I’ve been begging my mom to teach me since I was age 5. Every time she tries to teach me, she talks about watching her grandma wrap dumplings with lightning hands. Grandma would be like “get out of the way” until all that was left were the little dregs of rice and leaves that were too skinny or short to use, and that’s when she would let the kids learn. My mom would try by wrapping with all the leftover rice and messed up leaves, making little, tiny dumplings. And that’s mostly the way I’ve tried to learn over the years. It wasn’t until this year that I moved on to full-sized dumplings!

My great grandmother taught my mom how to make these dumplings because she was my mother’s main caretaker during the Cultural Revolution. My mom’s mom had to work in the fields during that time and my grandpa, my mom’s dad, was working at a factory in Hong Kong. He would send home money and try to visit when he was allowed to.

My mom’s name is Fook Siu Wong in Chinese, which means blessing smile. If you met my mom, she is a sweet little mom, but she’s fierce, very resilient— a very strong woman. She migrated to Hong Kong when she was 17 by hiking through the woods for 11 days. She lost 20 pounds in those 11 days. They survived by eating a rudimentary version of power bars: flour, sugar, and pork lard they kneaded into these tubes they carried in their backpack. They rationed out their portions: “Today I will eat only 2 inches of this.” They drank water from random puddles and shit. When I think back to what I was doing when I was 17, I was not doing that. My mom figures shit out. When she moved to America and missed eating a certain thing, she just figured out how to make it. She’s had to do that her whole life, figure shit out. She’s an amazing gardener and a great cook. Food is her main love language. That can be confusing and annoying when you just need a hug or someone to listen. But when you are hungry, it’s the best thing.

I remember eating zong every year since whatever year I can first remember. One thing I love about my family—they are really into food rituals. Every dragon boat festival there has always been dumplings. Every moon festival my parents make moon cakes from scratch. And every New Year, they make mochi rice cakes and rice mochi soup. Every meaningful holiday in my family was also a meaningful food day, and that was a deep part of how we kept track of time and how the cycles of the year went by.

The importance of food to my parents was something I took for granted until I got older. Other members of the Chinese community would remark on how dedicated my parents were to keeping up with tradition and how good their renditions of these foods were. It is something very particular to my parents—they are both the kinds of people who want to keep those traditions alive and are almost obsessive about getting it right. Case in point: when you make moon cakes you have to make a sugar syrup to mix with the dough to keep the outside from splitting, but it has to be a perfect ratio between sugar, water, and I think vinegar or something. You not only have to get the proportions right, but the temperature at which you cook it and the viscosity of the final product. My dad would spend hours and hours trying to make it just right. From year to year he would take exact measurements and keep notes of how it worked out in the moon cakes.

I took for granted that I come from such devout food historians. In my eyes, being a real matriarchal woman leader and a keeper of food history is being able to make 300 of these dumplings to pass to every Chinese person you know who might miss eating this flavor. People would always say, “I wait for your mom’s dumplings every year, and of all the people I get them from, your mom’s are my favorite!” My parents lost a lot when they left China and then Hong Kong. They were very young—they left in the late 1970s, early 80s. Back then, if you moved across the ocean, you knew you wouldn’t see your family again for 10 to 15 years. And so in a way I wonder if their obsessions with keeping these traditions alive is to reconcile the things they had to walk away from with the things they could remake.

The recipe on the surface is straight forward, but there are so many things you need to be an expert in to get it right.

First, there’s this bamboo leaf you wrap them in. To make these right, you even need to know which ones are “good.” Every year, the Chinese ladies in Portland will be like, “the store on 82nd and Division has the best leaves this year because they’re fresh and this specific kind of bamboo leaf.” You need to be able to know what is a high-quality bamboo leaf that is pristine and fresh. High quality leaves are going to be easier to wrap because they’ll reconstitute in water better, break less, and have more flavor. First, you soak the leaves overnight.

Then you get to the fillings. Everyone has their particular brand of sticky rice. My mom likes the one that has that big beautiful abstract red rose thing on it. You soak the rice until you can pinch a grain of rice and it will kind of break in half between your fingers. You then soak some split mung beans and salt them.

Every rice dumpling has some kind of fatty meat product in it so that when it gets steamed the oil from the meat will soak into the rice and beans. My mom will cure her own five spice bacon for the inside of it! So that’s another thing. Every little piece of this recipe requires the know-how of the person making it. Though it’s just rice and some other stuff wrapped in a leaf, it quietly shows off the expertise of the cook because of the careful consideration of every ingredient. She’ll also put in a sliver of Chinese sausage and some fresh peanuts.

The way you wrap the dumpling together also shows what a good cook you are. Wrapping the dumplings is incredibly complicated. You’re basically folding origami as it’s trying to hold all of these small different ingredients. At any point while you’re wrapping, if your hand slips, all the ingredients can drop onto the floor into a wet uncooked pile. That’s why we wrap perched on little, tiny stools over a big bowl, to catch the inevitable dumpling that will unravel in our hands.

And I haven’t even gotten to making the dumplings look nice. Ideally your corners will be sharp and your string work really beautiful to look at, no lopsided dumplings. Then you have to place them all in a pot and steam them for hours, and the ones that are not wrapped well will explode or leak everywhere. That’s sad, when you open up a pot to see a bunch of rice porridge sludge, after all that work wrapping your dumplings!

And then ideally after they are cooked, when you open the wrapper, the outside of the dumpling should be snow white so none of the filling is showing. You cut it in half and see this pale-yellow full moon of the mung bean, and inside of that is a couple pieces of meat. The peanuts go on the outside of the dumpling. If you can line up your peanuts so that after you steam and open it the peanuts are still perfectly lined up, it shows you are an expert at wrapping them.

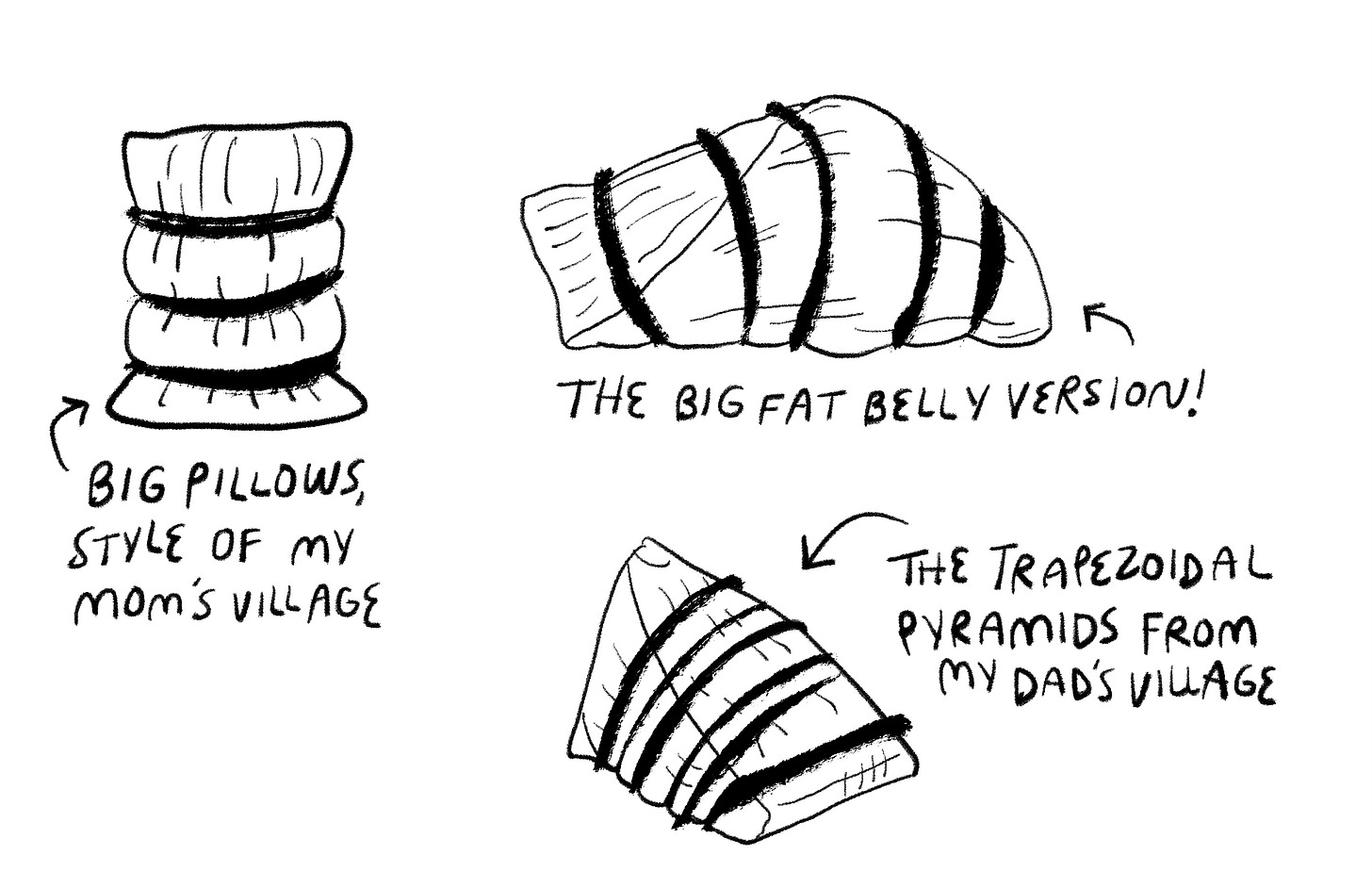

There are many styles of zongzi. The way you wrap your dumpling is very regional. There is a way to wrap with three leaves—one on the middle, two on each side, so it’s almost like a pillow. And then there is a second way where my dad is from; they wrap it on this beautiful oblique angle, created by two bamboo leaves that you fold into almost an ice cream cone on the bottom with two wings v-ing out on either side. You fold another leaf in an inverted cone over this and then with some magic handling, you fold it over on itself to make a trapezoidal kind of pyramid.

The third kind my family wraps is a form that my mom has not mastered yet. You go back to the original pillow shape but there is an extra cone shape in the middle of the pillow. It looks like the pillow has a big fat belly coming out of it. My mom at age 65 is still trying to figure out how to wrap that one.

When you eat a hot one of these dumplings fresh out of the steamer, it wafts out this floral green ricey air. A bamboo smell. And then you cut it open and the mung bean inside is silky with the fat of the meat that’s been oozing out.

In my family, the way my mom grew up eating them, they would sprinkle the lightest dusting of white sugar after you open it. This is super decadent to her; when she was a kid, white sugar was so rare. The sprinkle of sugar adds a little crunch to it and offsets the salty five spice meat in the middle.

This is why this is the recipe that shows if you are a real adult in my family. You have to master all these little things: snow white on the outside, perfect proportion of the ingredients on the inside that are perfectly cooked and wrapped with expert hands with perfect sharp little corners and beautifully tied up with string like a bow on a present. And to top it all off, you make like 300 of them and hand them out to your friends and community. In my eyes, in the love languages of my family and family culture, this is your big rite of passage!

This year I progressed to wrapping full-sized dumplings. But now, even though I can do that, there are all these other parts of the recipe I need to learn and be able to master. I think a part of me is afraid of making this recipe alone someday because it will signify the big change of when my mom is not here anymore. As I get older, I feel the big crunch of, “I need to be able to make these because my teacher is not going to be around forever.” And this goes back to the power of a family food like this: It can mean so much in terms of how you remember or carry something on in your family.