Hello friends,

I’ll be honest—I’ve been in a professional malaise. I want to blame the smothering misery of our political moment. And that’s a partial truth. At this exact moment, my brain is leadened by ICE raids, Israel (with US backing) inciting a regional war, and the ongoing loss of Palestinian life. But there’s something related, overlapping, but distinct happening: I’m in a transitional moment in my life.

For some time, I’ve been trying to find my way after both the Umi fire, which happened almost a year ago, and the publication of Group Living last August. Umi has restarted and we’re making noodles for schools and a few restaurants, but we’re smaller in size and Umi represents a smaller fraction of my income and time. I’ve begun researching a second book, but its form remains fuzzy, and this process will take time and invoke mystery. I’ve needed more paid work and been lucky to get contracts writing for people I admire. But in the grander sense, I’m left wondering about my professional future.

Lately, my concern has taken the form of this surging question: What can I do to earn enough money to make time for writing, organizing, dreaming, playing hoops, tending a garden, making ice cream cakes, caring for my elders, going out to my favorite lunch spots, sitting on the floor with my friends doing nothing, and, most of all, growing old? Uh oh! My priorities have veered out of the career lane. For who has the time or energy to reimagine their career when they’re busy writing, organizing, dreaming, playing hoops, tending a garden, making ice cream cakes, et al.

I’m forty! Isn’t this supposed to be my professional ascent? Am I misreading the moment, assuming I’m doing it wrong when I’m doing it fine? Or assuming it’s fine when in fact the time for movement is now?

This week, I started to feel more clarity and calm. When I feel this way, I want to write! Over these quiet months, I’ve been collecting so many things to tell you! But today, I’m simply going to let myself write about what’s most recently on my mind. I’ve missed you. I’ll try to write again soon.

My Mom’s Death Tour

For some years now, I’ve noticed that my mom has been on what I call her “Death Tour.” Slowly, methodically, she’s been visiting dear friends and family members she may never see again. She’ll announce, “Oh, I have to visit X before he dies, or before I do!” and the trip planning will begin. The necessity for this amplified last year after she had two heart operations. After the surgeries, she visibly slowed down. I’m used to my mom flitting around like a hummingbird extracting nectar in a wildflower meadow so even this modest deceleration has been emotional for me. As she tells it, she’s “80 minus 1.” I’m scared to lose her. That said, she remains strong, funny, and visionary. I take her insistence on the possible nearness of death seriously and join her on these visits when I can.

Recently, we drove down to Humboldt County in the Northern California Redwoods. It felt like driving back in time. I’ve done this drive occasionally throughout my life so when we reached Grants Pass and then hugged the Smith River, I remembered being with my dad as a ten-year-old in a golden Jeep, agog at the beautiful green pools. Then I recall only a flash of memory, being on this road with my mom as a teen, uncomfortable flip flops abrading the skin between my toes.

The route cuts off I-5 on a diagonal toward the coast and enters California within its redwood forests. This also gives me a sense of time travel because the grandma and grandpa cedars are as much as 2,000 years old. They eclipse me, my mom, and our car on every scale. This time, I drove us down Howland Hill, a gravel drive that leads through some of the grandest redwood stands in the National Park. Halfway, we parked, took a hike, left the trail even though a sign told us not to, and my mom smoked weed along Mill Creek as we both sat in calm awe.

When we exited Howland Hill into a grove of standard second-growth fir, the trees looked so spindly and small compared to the redwood cedars that my mom cried out, “Look! They’re all dinked out!”

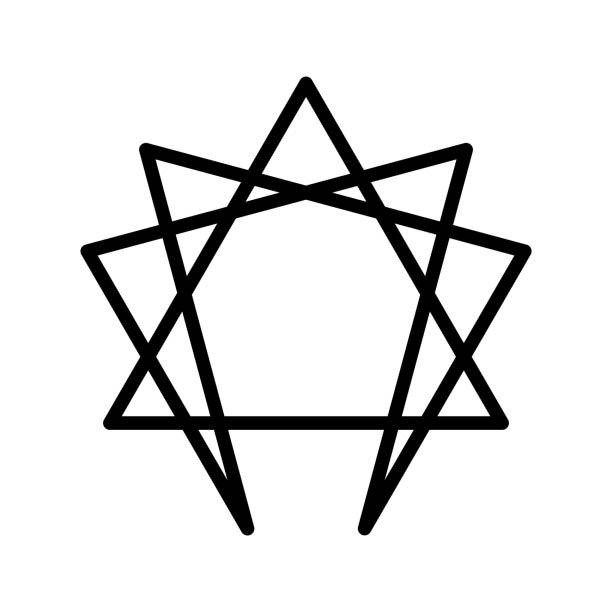

Upon arriving at my mom’s friend’s home, I experienced another slippage in the fabric of reality. I expected this. I’ve been here a few times, and each visit, I experience Fred and Leah’s home as a time capsule to 1970, when they built it. The home sits on forty hillside acres overlooking the King Mountain Range and belongs in a fairy tale. The original structure is a wooden geometric enneagram—a nine-sided star polygon—inspired by the esotericism of spiritual leader G.I. Gurdjieff. In other words, it is wonky, nonconformist, and oddly mystical.

They’ve added to it so there are unusual rooms attached here and there, obscuring the original shape and somehow making the house even wonkier.

The garden is verdant and overgrown in an outlandish way. Bits of siding lean against the house as though they’ve been waiting to be installed for decades. An outbuilding that used to be an extra bedroom has been reclaimed by the garden jungle.

Inside, the place smells of Brewer’s yeast and overripe cherries. There’s a two-gallon jar filled with soybeans, something I haven’t seen in a home in years, and a poster for “psychocalisthenics,” which look like very practical PT exercises. Our first night, we eat polenta topped with chicken and black beans—a one-dish potluck!

My mom was close with Fred and Leah in her early twenties, which coincided with the mid- to late-1960s. Both Fred and Leah were actors and playwrights. All of them took a wild amount of acid during this time, and Fred once told me he spent an afternoon trying to gather the largest bouquet he’d ever held, only to snap to when an old woman screamed out, “why are you cutting down my hyacinths!”

Back then, they wiled away the hours doing what may have felt like very little but was in fact a lot. The 1960s were a forge melting and reforming them into new humans. When my mom visits, she’s returning to those molten memories.

The last time we came here, we were also on our Death Tour—that time to see Fred before he died. My mom timed it just right and he passed not too long after. Leah told me that she’s incredibly lonely, but since he built and touched everything around her, she’s also never without him.

Fred was wildly charismatic, tall, long-limbed, boisterous, and affectionate. I remember him always having shoulder length greasy hair and a pert mustache. Leah has always been quieter. She wears her hair like my mom—thick and white, semi-brushed, and pulled into something wilder than a bun. No bra, wildly patterned stretch pants, slip-on shoes. Many times in her life she’s stopped speaking for forty days at a time. She has a very rich interior life she keeps secreted away and reveals in flashes through poems, plays, paintings, and other cyphers.

Fred and Leah moved to the area to escape Los Angeles. Leah chose it because she liked the way it smelled. And this area does smell good—like cedar and salt air and bay laurel. Like renewal. When they first arrived, they rented a home in a nearby town. They were immediately kicked out because the realtor was a shyster and the owner had no intentions of renting. The realtor moved them to another spot and lo and behold the same thing happened again! This unreliable man later became their good friend. Without a blush of embarrassment, my mom says that she developed a crush on him when she visited. This kind of story is common in their shared past: sketchy actors becoming dear friends, mischief as a beloved art form.

Fred and Leah found out about a piece of undeveloped land and put down every cent they had—which was almost nothing. That first summer, they lived outdoors. I asked if they erected a tent and Leah told me they slept in the open air under the stars. She was pregnant so Fred hustled to build their enneagram before winter. At one point, he found out about a load of wood and, since he was hitchhiking, convinced a truck driver to take him and it to their land an hour away. (I’m unclear if they owned a car at all!) They moved in by October.

Since they had no money to speak of—and this may be the story you were expecting—they took notice when a friend shared that he was making some money on the side selling a little of the weed they all grew. Leah tells me that for the next forty years, they grew 20 plants a year, sold that, and lived modestly. They both wrote plays and performed local theatre. They raised their kids. They were part of their community. Twenty plants a year. She told me it was a good life.

You also know what happens next. Legalization came with strict policies and investor-fueled competitors. Small growers were forced to scale up or go under. My mom wonders why they didn’t form a co-op—she would wonder this!—but I’m familiar with the way that some hippie back-to-the-land movements slip easily into libertarianism and rugged individualism. Each man for himself and keep the government out of it. They’d all moved off the grid for a reason. The explanation could also be simpler: they didn’t have the time.

Twenty plants a year. A good life. That was only possible at a very different economic juncture in history. I find it comical to imagine being pregnant and sleeping on a tarp outdoors with no shelter, but honestly, I find it even more staggering to imagine buying this land for roughly $10,000.

My mom and I were only in Humboldt for two nights and one very full day. It was brief, condensed. Another old friend, Ray, joined, and they all spent hours talking! I was mostly an observer in this scene. I’ve never known Ray or Leah well, so almost everything felt new to me. At one point, exhausted from driving most of the way, I took a nap and when I awoke, two hours later, they hadn’t moved an inch. My mom was asking Ray about whether she remembers correctly that he never washed his clothes back when they lived side-by-side. He confessed that clothes were cheap and so he’d wear them a few times and then let his friends take them and buy new ones.

“How cheap,” I suddenly burst in, and he said he couldn’t remember but nickels, dimes, maybe quarters. He told us that he worked for an insurance company investigating applicants before they received a policy and one day he was caught by the police high on heroin.

“How were you caught?” I asked.

“They found needle marks on my arm,” he said with an unreadable smile.

He was in jail for several days and when he came out, he tells us, his boss said, “Ray, you’re a good worker and I don’t want to fire you, but, well, it’s company policy!” He moved to Humboldt not too long after that.

My mom talked about when she went to jail for growing a single weed plant. Because they nabbed her on a Friday she was held for the weekend. During her first meal, the woman across from her asked what she was in for, and my mom explained about the plant. Then she returned the question, and the woman replied, “I killed my father.”

“Would you like my chocolate pudding,” my mom responded, sliding a small bowl her way.

Leah went to jail because a police officer pulled over the car she was in with two black friends. “He had no reason to arrest us,” she narrated with fury fresh in her voice, but he insisted they show a receipt for the cassette deck in their vehicle. It was clear to everyone they were pulled over because black men were with a white woman. She and one of the men spent the weekend in jail. Leah was obsessed with drawing crosses at the time and so in the shared women’s cell she drew them continuously and an older Latina, thinking she was simple, took her under her wing. The owner of the car was jailed for two weeks and then forced to sign a paper stating he hadn’t been detained.

These are the stories they tell. The beating heart of their friendship exists in this distant past. They’ve been largely absent from each other’s lives for fifty years. As a result, they know each other very well and not at all. This knowing-unknowing has a shape and flavor. Comfort with unease. Predictability with discovery. Dare I say it’s beautiful and sharp and mystical like a nine-pointed star and like the polygon formed within its points, where all lines of connection encompass a shared core. Or maybe it’s just a wild landscape, mostly untamed and unknown but beloved.

As we were leaving, Leah said, “so I’ll never see you again?”

I looked to my mom, whose expression was stunned. “No!” I suddenly cried out, although the entire point of this trip is that the answer is likely yes. “I’ll come back,” I added, which felt selfish.

I’m not ready for that level of finality, even among these people I don’t know well. And is my mom? She says she’s working on it, but by the alarm on her face at that question, I’m guessing she’s not there yet! And maybe that’s not the point of her Death Tour after all. It’s about how precious life is rather than how easy it is to let go.

We drove home exactly the way we’d come, returning to the present. Before we’d left for California, I’d felt lethargic and aimless. When I looked in the mirror, I swear every feature on my face was tilted 3% in the wrong direction, all in different directions. Something about me was very off! This quick trip gave me the vitality I’ve been missing. Hours in the car. Sleeping in a slanted van (their driveway had no flat areas). Forgetting to shower. Time travel. It didn’t matter. Miraculously, even though we’d spent so much time in the past, these days with my mom and her friends felt fresh and revivifying.

“I never thought I’d live to be this old,” my mom had announced at some point during their reminiscences. And later, “Could you see this far into the future?” to which Leah said, plainly, “no.” Nothing about their shared past resembles my own, but when Leah answered, I felt sudden kinship. I can’t see into my future, either. And we share something else: I love my friends as much as they’ve loved each other. Things may not be easy, but our lives will contain more mystery than we can fathom. I’m feeling a new gratitude for the mystery.

A Few Updates

This Wednesday, June 18, I’ll be in conversation with Bridget Crocker, author of The River’s Daughter, at Powell’s. Please join if you love rafting, high adventure, memoirs that don’t look away from trauma, and lyrical descriptions of riverbanks.

My friend Andrew Barton released a lovely commune cookbook homage this year called Free Food: earth eating. It’s full of natural foods lore, his memories of the Eugene, Oregon businesses that anchored his childhood, and recipes for all those hippie foods you secretly crave: grain salads, beet hummus, carrot-ginger soup, and mushroom pie in a nut crust! I have a short essay within. Get a copy for yourself and the freewheeling, bulk-bin-loving home cooks in your life.

The new issue of Kitchen Table Magazine is themed around The Future and includes a Q&A with many Portlanders—including me!—about visionary glimpses into that unknown terrain. Pick one up at shops around the city or online.

Edible East Bay recently published a review of Group Living and Other Recipes. I wrote for Edible Portland for years so being back within that universe feels tender.

This turned out long! Forgive me. It feels good to be back writing here again. See you soon!

I have a project for you. Let‘s have lunch one of these days and I’ll tell you about it. I‘m considering calling it “seasonal“

Beautiful and deeply comforting to read. Thank you, Lola! I hope the malaise (I'm feeling it too) gives way to new mysteries soon...