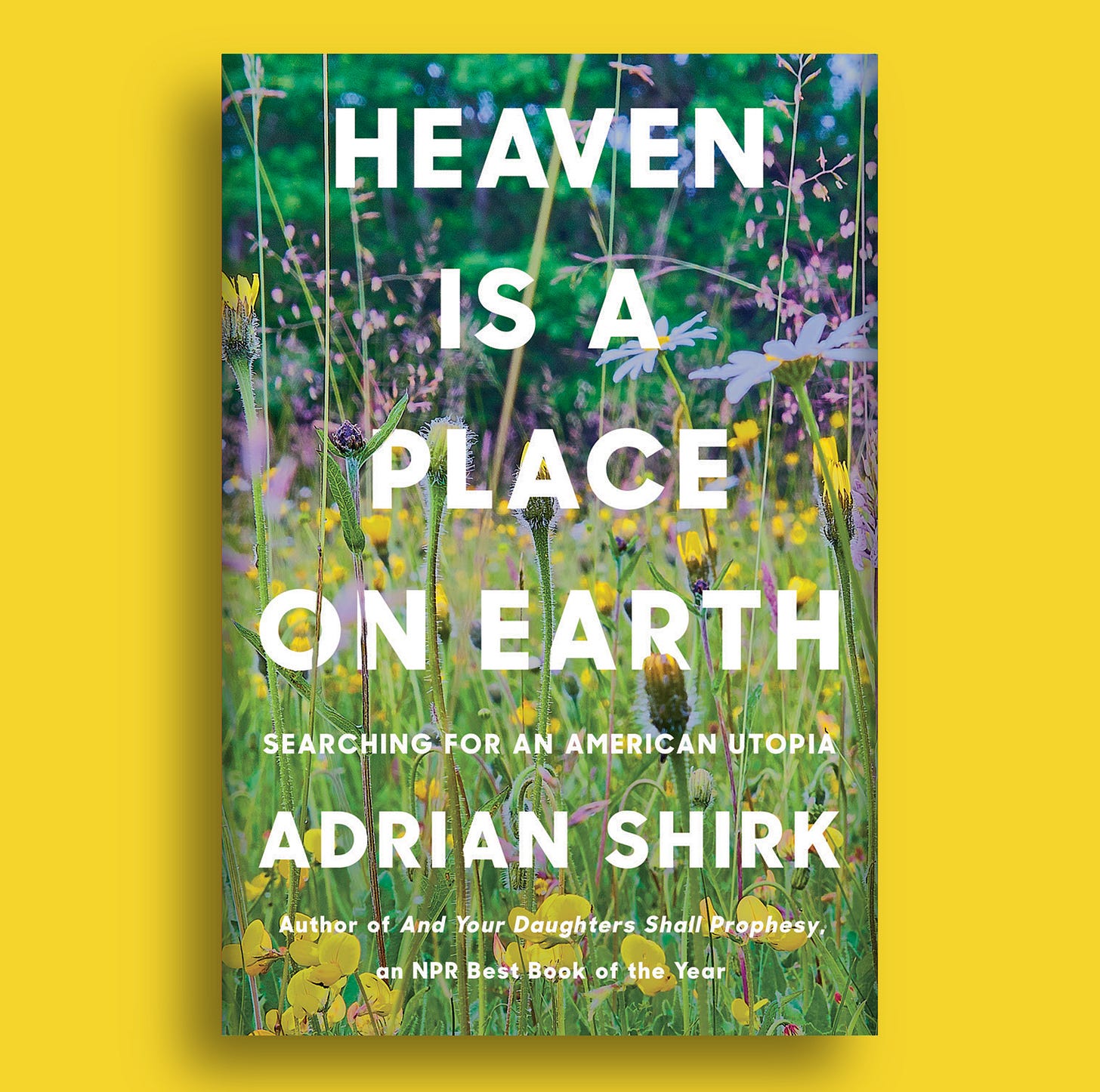

Heaven is a Place on Earth

A conversation with author Adrian Shirk about utopianism, layered histories, the magic of the Sou'Wester, and group living

I was on the ferry from Whidbey Island to Port Townsend, Washington in early March of this year, after a two-week writing residency, still feeling soft and squishy from the alternate reality of life inside a cocoon. While on Whidbey, I’d been writing about my uncle Doug’s anti-military and anti-nuclear protests. Sitting in the ferry, as the boat’s squared bow cut a path through the water, I could see the multiple realities he was always trying to show me piling on top of each other: all the beauty of this place, with its cool sea salt air, nobby hills, and weather-worn wooden houses across the water; and alongside it, a giant military weapons loading station with a massive ship that, from the distance, looked the same size and style as a Battleship toy, like I could pluck it from the water and deposit it someplace else. Here was a place many people consider heavenly. Here was a place inextricable from war and conquest. I started scrolling through my phone and the title of a book jumped out at me from an email I’d received from Counterpoint Press, almost like it were pulsing and neon: Heaven is a Place on Earth: Searching for an American Utopia by Adrian Shirk. I ordered it on the spot, on the boat, coursing towards Port Townsend.

I read Adrian’s book in a sprint. Although it’s dense, I found it hard to put down! It turns out that Adrian is from Portland, a little younger than me, cooked in a cauldron not so different from the one I was boiled in. Through much of the book, Adrian explores the history of utopian experimentation in the U.S. across the centuries, and the stories she recounts are fascinating and strange! I was especially riveted by her telling of the various fringe Christian groups in the 18th and 19th centuries and the utopian groupies who documented them, and her recounting of the colonial history in Portland (she’s the descendent of Captain Couch, of Couch Street in Portland, pronounced kooch). But the book is also a personal account of her search for a communal life outside of and in sharp contrast to her stressful existence living in the Bronx, working as a professor at Pratt, trying to be a caretaker with her husband of his very sick father, and feeling ground up and spit out by wage earning. Her search through history is also a search for her own future.

A few months ago, feeling like the book hadn’t let me go, I reached out to Adrian to ask if she’d have a conversation with me. Her book’s terrain is different from what I’ve been writing about related to group living, but there are many overlaps, and in ways I’m still processing, her book reframed how I’ve been thinking about legacy, memory, and inheritance.

We ended up talking for hours, and I’m sure we could have talked for hours more! What follows are condensed excerpts from our conversation.

Lola: There’s this moment late in the book where you say a very assertive statement: I did not come here to tell a happy story. And that feels true to me. Throughout the book, you talk about all kinds of complex social structural issues around racism, classism, sexism. But there is something innately hopeful in the conception of the book, I think, which is that you’re constantly finding utopia. You find it in very unexpected places: we’re at Robert Moses’ grave; we’re in Bolinas, California; we’re with our friends. You’re always searching, and you’re always finding. So what are you finding?

Adrian: It’s a great question. I was trying to use [utopia] as cleanly as a descriptive term as possible. And what that meant was using it as a category that indicated that something was created or had happened or was happening that was not supposed to be able to happen [based on] the economic imperial structures or powers… This thing, this enterprise, this community was defying in some way, whether short term or long term, all of these strictures or supposed limitations. I was trying to look at examples that I found particularly compelling. I was open handed about that. It was a very personal list of communities and enterprises and examples that I was attracted to for different reasons.

I think the other thing inherent in various personal and historical associations with utopia or utopianism is something that is seeking based, something that is sought in part because it is linguistically “no place.” [Utopia translates from the Ancient Greek as “no place.”] And yet it is also the thing that is consistently, eternally pursued. I think that also speaks to what you were talking about, this tension in the book [and in the conception of utopia, between] these ideas of hope and tragedy. And actually, even more extreme perhaps: persistent, unabated hope and absolutely, certain tragedy and failure. The material utopian history is the movement that generates from that tension, which is the searching.

What it is I am always finding, whether it’s something from the 18th century or something right around the corner from where I live, appears to me to be animated by those two principles, as well as embodying something happening where no one’s subjugation or exploitation is contingent on the thing and no one’s making a profit and some need is being met. Maybe those are the three principles, but honestly that’s even a little strict. But if I reveal my metric, maybe that’s the thing I’m constantly finding.

Lola: That feeds into something I found really rich to think about: you sort of put on parallel tracks utopianism in America and carceral systems and prisons. We have been a hotbed for both of these things. Can you talk about that connection, and your discovery of that connection?

Adrian: There were multiple times that I was doing very casual research—I was going to different sites including, but not limited to, a former Shaker colony, the former site of Black Mountain College, the liminal present past site of Soul City. These are three pretty significant examples in the book of American utopian history. And in those places, prisons had been built—on these particular parcels of land where this particular kind of activity had happened. The starkness of that was something I continued to note.

The way that I work and think is not really as a rigorous researcher, but more like a poet or even like a visual artist where I’m moving things around until they form a kind of meaning. The persistence of that layering brought forth what should have been a somewhat obvious connection to me at the time, which is that this is a nation whose ethos was built on the idea, though not the practice, of building the world anew, of casting away from whence one came—not needing history, not needing coherency, not needing lineage, not needing to retain the inscription of time or folk culture or the indigenous history upon which it was all built and whose genocide the construction of that dream was built upon. That idea, that energy [of building the world anew] was in a way value neutral: not a good thing and not a bad thing. It has the equal capacity to be marshaled into both an agent of enormous horror and also liberation and innovation. Why is that important? The idea that a utopian community can, in the blink of an eye, become the basis for the carceral state, that a utopian community can become, in the blink of an eye, one of the most major machines of violence and inequity and exploitation that the world has ever seen, should let us know that the pursuit of utopianism necessarily requires a constant accounting, a constant accountability, a real insistence that no solution or idea or possibility is ever a permanent arrival. That forces us to have to be present. We still have to apply rigorous moral accounting. Nothing is ever resolved.

Lola: I think you’re talking about something that was one of my favorite personal takeaways of the book, which was this idea that transience, impermanence, this is an asset and a virtue…

You mentioned at some point this layering of utopian communities on certain pieces of land. One place ends up with this recurring exploration. What is it about certain places that causes that layering?

Adrian: The questions that I have found myself poised to be asked in the process of writing and promoting this book are questions that I’m like: is that even answerable? Which I think is so funny. What would it mean to think about the possibility that certain pieces of land or certain kinds of areas for some reason or a series of reasons draw this utopian palimpsest unto themselves? Why hasn’t that been the case for every single cooperative enterprise that’s occupied a piece of land in that way?

Adrian pondered the density of utopian experiments in the greater Appalachian chain from the Catskills down to the Poconos as well as in Western New York—how the geography and history of those places might inspire communal enterprises—but ended inconclusively.

[I wrote these] short pieces of uncategorized field notes, my constant observations of utopian activity in my midst [called Utopia Notes, these brief interludes are sprinkled throughout the book like snapshots]. I included a Utopia Note in my book about the Sou’wester, which was a place with this really odd assemblage of community activities and a beach lodging out on the remote Washington Peninsula. My family and I used to stay there when I was a kid in exchange for my mom doing flute performances. [She had] a long, 40 year friendship with the [previous] owners who are this older retired South African Jewish couple who had owned it from the early 1980s. I recently went back to the Sou’wester for the first time in 15 years. I had not been there since they [sold] it. And this woman, [Thandi], had taken over and had been building on this amazing legacy and continued to build out this beautiful place. She’s got a crew of people living and tending to all these different activities. There’s a Montessori school; there’s an artist residency; there’s tons of community activities. It’s continued to be an amazing kind of utopian model. I was there for an artist residency, and we were doing this big opening meet and greet, and [I learned that the new owner, Thandi,] is also South African Jewish and [comes from] a really similar familial diaspora to the former owners. They didn’t know that when she bought the property.

Lola: Thandi is a friend! The Sou’wester was also the home of a U.S. senator [Henry Corbett of the Oregon territory], so there is that quality of having co-opted what was a place of power for this more communal thing.

Adrian: Totally, thank you. That’s such a crucial element to this story, which is: It was a senator’s 19th century estate during some of the most fascist colonizing of the Pacific Northwest. What does it mean to look at these pieces of land where there are these cycles, these lineages? When you trace them back, sometimes the cycles look like this kind of wily, wild restoration. And I guess this is partly what’s so compelling to me about looking at history through the lens of just utopianism. It indicates that this extraordinary, unforeseeable restoration and reclamation is always a possibility, but that the story is never over.

Lola: Thandi is such a badass. She holds down something I would describe almost as strict that allows people to kind of work inside of a system, but then contribute and receive something. So it is coherent, even though there’s something about Sou’wester that can feel deeply chaotic.

Adrian: It is often the spirit of one person being like: okay, I’m conversant enough of this project or this place or whatever [and] I can provide this exact kind of rigidity that will produce the maximum amount of flexibility and abundance, but if I don’t do that, if that rigidity or that strictness isn’t there, it falls apart. It’s not about control necessarily. It’s structural.

Lola: I think about charisma and vision and the way individuals often hold it.

Adrian: There’s obviously so many utopian communities and experiments that have resulted in an accumulation of power that results in similar patterns of abuse and exploitation. Therefore, doesn’t a utopian experiment necessarily need to be radically distributive in terms of its power structure or radically, rigorously cooperative? There are lots of models of that and those are really interesting to look at, too. Twin Oaks in Virginia. There’s an amazing, longstanding intentional community that has in a lot of ways functioned with a great deal of integrity, but it’s a full time job in terms of the amount of energy required and the personalities required.

Lola: Yeah. Are you willing to be a bureaucrat?

Adrian: Right, and devote many hours of your week to the integrity of its functioning? Is your buy-in enough that you’re willing to do that for a decade or two decades?

There are a lot of wonderful examples of rigorously distributed, rigorously cooperative enterprises, which actually come down to one or two people retaining the vision or structure, which I think acknowledges to some extent, in terms of utopian experimentation, the way in which everyone’s need or desire or buy-in is not equal.

Lola: I’m at a very tender part of writing my own piece, which is that I haven’t written the end of it, and I’m having profound self-doubt about everything that came before. I had this hope that as I wrote, the ideas would solidify. I thought: I’m just going to write through it and see what happens. And here I am, coming to the end, and I’m not sure where I am. How did the last part of writing go for you? How did the ideas scaffold themselves for you near the end? Did you go back through and reevaluate what had come before, or did you accept the learning as it went? Did it go sequentially?

Adrian: When I look back, I think there were three phases. [First,] there was the notes phase, which lasted honestly a decade. I made a physical cache of notes of all forms that eventually I came to understand as notes toward or around American utopian experimentation. But there was some long period where I wasn’t able to articulate that that’s what it was. I knew finally at a certain point: Okay, there’s a body of curiosity and there’s actually language. Graphomania is my main strength as a writer. [I’m] constantly writing, constantly, on whatever medium might be available. That’s helped me relate to my own writing less preciously because there’s just a lot of it. Most of it’s crazy and garbage and nonsensical. The meaning and the beauty will be pulled and culled from that.

The notes constitute a lot of what I ultimately decided to do more focused research on. So that’s the first third. It’s not conscious and it’s not scaffolded in any way that’s apparent to me as an ego.

And then there was this middle portion, which is the worst and the most unhelpful. I really start to consciously think about it as a structure. That’s the most painful and the most confusing and honestly when most of the wrong choices are made. That’s when it starts to be fleshed out. Where do we want to go? Who do we want to talk to? How much space do we want to build in for that? How do we even know until we know? I bump up against a lot of my own walls. But it does start to create, through a great strain, a shape that will change.

The end of that second phase is when I came up with the “Utopia Notes” sections. I knew that there was something about provisionality and liminality that felt important and that I wanted to formally represent.

With the living sections [the autobiographical parts], the idea was: OK, what if you included some of these narratives in the way that it actually felt. There was no clear meaning mapped on. These were genuinely mysterious periods. [In writing it, I kept asking myself:] Why are we here? Which is always the question about braiding personal narrative into research. Because you’re like: well, why did you pause? Why did you say that you went to the bathroom? If you're going to say that you ate this breakfast, why not say all the breakfasts or none of them? What is important in life? [Eventually, I decided:] What if you let that sense of layering and braid actually happen as an aesthetic experience for people as they read? You don’t have to grip them with meaning because meaning will be made.

And then the third part is the most thrilling. That’s when I have some clarity about what I still want to learn. There’s a little more energy. I’m getting a clearer sense of what I’m actually looking at and how big it is, how it connects to all these other conversations in the world and in my own life. Then, it’s a quest. It is also at the very end of that third phase that I felt like: Oh, that’s what I was trying to say. Like, oh my God, it’s so interesting that this thing seems to be conversant [with this other thing]. It’s as though I realized that much longer ago than I did.

Lola: At the end of the book, you get something that you wanted: a communal life. This isn’t a book about ever arriving anywhere, but you have arrived somewhere. What have you found in getting this thing that you wanted?

Adrian: [I’ve learned] something about the necessity of never treating anything as too precious, never treating any one of your own ideas or thoughts or hopes as too precious. You get to this moment where you get what you search for. Maybe it doesn’t come in the way that you are searching, [but you are] living in community… We ended up buying a 65 acre piece of land with a huge farmhouse and a big two floor outbuilding below market rate, which had almost immediately been marshaled into emergency housing for the pandemic. [This property] accomplishes all these different possible things. Immediately, we kind of developed an artist residency program just by inviting a huge network of people. All of our peers were under-remunerated laborers. They were teachers or artists or organizers, scholars or theologians or therapists or social workers—a lot of people doing lots of work who were never going to be able to acquire or develop anything like this [alone]. But together we could give it to ourselves. Several months after the initial hit of the pandemic, we were able to open it up to some of its original uses. So there was this mix of long and short term tenancy. Everyone made some small contribution that made it so that everyone’s overhead was really low.

There was a massive traumatic rupture resulting in my divorcing my husband, and so the last two year period has been a kind of learning: What were the things that were really difficult or dysfunctional? What were the things that felt really useful? At that point, I found myself managing a collective resource [for no income]. Adrian talks about wanting to get away from the role of property manager.

[Now,] there is this core of ten people, three of whom live there [full-time], seven of whom don’t, but who all have a monthly buy in. They can also bring in other collaborators. Everyone has ownership over their own activities. I am the centerpiece functionally because I’m the landowner. But [I wanted to] create a clarity around what resources we all hold in common. And so we created a user’s guide [to living and being in the space.] People who come in are no longer coming as guests or visitors. This has been very key and felt very countercultural because there are not that many spaces in the world where you show up and there’s not a host and you’re not a guest. We have not developed the muscle for what the alternative is other than being hosted or being a guest. The last two years have been the most fun I’ve had. It’s not perfectly equal obviously because I am living under speculative real estate, but there has been this sense of shared ownership over experiences. People are then able to have an enormous range of social and collaborative experiences and encounters, but also have a lot of freedom to be alone and invisible and unmarked.

Some of the things that have been most interesting to me about communal living or cooperative activities have been the necessity of aloneness and togetherness. The rigidity of the bylaws [and user’s guide] that are rigorously developed allows for maximum freedom and flexibility. This is going to be a lifelong inquiry I think for me: how to create the conditions to feel like you can show up. If we’re poised to acculturate ourselves to constantly evaluate: what is the best thing now? What needs to evolve? When is cooperative or democratized decision making really useful and ethical and expedient and when are we making an idol of it? The idea that there is any modality that will prevent us from experiencing harm, danger, strife, whatever, is absurd.

Lola: What else are you working on that you want other people to know about?

Adrian: I will say something about living in a deeply shifting communal context has profoundly changed the way I’ve worked as an artist in the last couple of years. What I’m working on these days is collaborative, devising theater pieces and plays with a group of women, collaborating with musicians [and] filmmakers in relationship to text that I’m either making for an occasion or I’ve been developing. I feel like over the last couple of years, my entire relationship to writing has changed a great deal because of this constant daily vision of people working in an ecosystem, which is not a fixed ecosystem.

I’m going to leave it hanging there! Check out Heaven is a Place on Earth: Searching for an American Utopia. Adrian is also working on an audio version of the book, which should be released this fall. Follow her work at adrianshirk.com.